Milton Dickson, who was born in 1950, was repairing shoes with his dad before turning ten. His two great uncles ran a shoe repair shop in Walterboro, and his father ran one in Ridgeland. Milton says he’s not sure how long his family has been cobblers.

“There might have been some earlier than my great uncles, but we don’t have enough family history to be sure. I know we’ve been fixing shoes for at least five generations,” he says.

His father eventually opened a shop near the family home in Branchville. Milton and his two brothers began working Fridays after school and Saturdays helping with the work load. After his dad opened a shop in Orangeburg, Milton’s mother began working there, and Milton added some shifts while attending Orangeburg-Calhoun Technical College. He’d decided to find a different way to make a living.

After graduating with a degree in drafting and design, young Milton found a position with Smith Corona and was ready to move on from resoling shoes. Two things kept that from happening. One was the company’s insistence that he move to Oakland, California. The other issue was cubicles.

“In this job I can talk to people while I work for as long as I need to—meet different kinds of people. In the world of cubicles, you weren’t supposed to even talk. I decided to stay where I was,” he said.

When his father required back surgery, Milton began working in the Orangeburg shop full time and stayed there for 30 years. Eventually, a shoe salesman told Milton he needed to buy a struggling shop in Columbia. After steadfastly refusing to move to Columbia, Milton finally bought the existing shop that “needed some help to survive” and began a career in Columbia. He left the Orangeburg location to “Momma and my two brothers.”

Milton’s son, Oakley, finished high school while working with his dad and then attended Liberty University. After graduation he came home to sell homes, but the economy at the time wasn’t good for that, so he joined Milton’s shop, working full time.

Before long, Oakley decided he wanted his own business so they found a shoe shop in Five Points for him. After several years that location began struggling due to Five Points construction issues, so Oakley moved to a shop on Main Street. He also began serving as a part-time youth pastor.

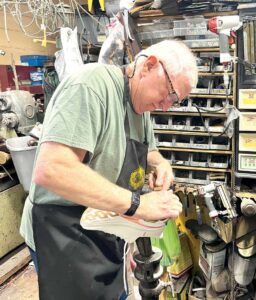

When the church elevated Oakley’s youth pastor position to full time, “like a good daddy I took it over and ran it until my heart attack,” says Milton. He sold the shop to a former helper, who eventually sold it back to Oakley. That Main Street location now operates as Dickson Brothers Shoe and Leather Care. Milton spends his working hours at Dickson’s Old Cobbler Shoe Repair at 6358 St. Andrews Road and talks as much as he wants.

For as long as humans have had feet they’ve covered those feet in some kind of animal skin. Leather processing and shaping that leather into a usable product has been part of human civilization since before humans were civilized. Every documented level of human existence has featured people who make and repair shoes.

Both Rome and Egypt had respected artisans capable of building and repairing shoes. In some places, like England, shoemakers were known as cordwainers, and their work was so valued that guilds were formed to regulate the industry.

The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century brought significant changes to the industry. Mass production of shoes in factories led to a decline in the demand for traditional cobblers, as factory-made shoes became more affordable.

The widespread use of plastic and synthetic materials in footwear has further impacted the cobbling profession. An American industry featuring around 120,000 cobblers in 1950 has been reduced significantly today. Best estimates figure there are between 6,000 and 7,000 left.

A rapidly growing population creates issues for leather consumption and processing as it has for many other industries. Animal welfare, workers’ rights, and environmental pollution, along with waste management, are now part of everyday life for leather artisans.

Milton understands those challenges but says he wishes the government would get behind the idea of putting more educational emphasis on cobblers and other jobs that were once popular with young people just finishing high school.

“I had several kids from high school work part-time for me during their time in school. Every one of them told me this was the best job they ever had,” he says. “America is filled with occupations that don’t require an expensive education or a lifetime in a cubicle. But the people needing jobs and the jobs needing workers don’t seem to be connecting.”

Milton had a second heart attack recently. The health setback and a road to recovery brought up questions about continuing to work. “When I had my first heart attack it took three days of being home before I realized I was not doing that,” he said.

It doesn’t take very long to notice Milton likes his work and enjoys customer interaction immensely. He is efficient at repairing anything that uses leather. He also understands he hasn’t built a loyal following alone.

“I need to remember my wife, Amy, and daughters, Kayla and Ashlyn, along with all the other people who have worked with me over the years are equally responsible for this shop being so successful,” Milton says.

Besides he has another consultant when thinking about retirement.

“God didn’t tell me to retire, and he ain’t took me home yet,” he says.

So he’s staying around—at least for a while.

Loading Comments